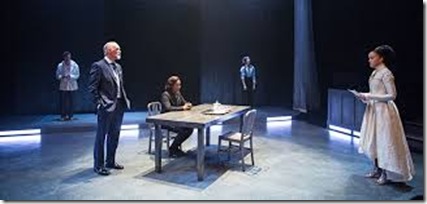

Hennig’s latest Tudor Thriller as staged in Stratford 2017

The Virgin Trial. Photo Cylla von Tiedemann

I decided to post this review as well because of the background detail that could interest the public. A.R.

STRATFORD, Ont. — Tudor England in all its drama and turbulence continues to attract a huge following in today’s popular culture. From the reign of King Henry Vlll through to the Gloriana days of Elizabeth 1, we’ve had an unending cycle of popular and academic history, best-selling fiction, movies, television series and stage plays.

It’s inevitable that we often get more mythology than history and that the speculative often vies with the factual for our attention. Purists may harrumph about this — will we, for example, ever know for certain the truth about Elizabeth’s virginity? But can we deny that, even centuries afterwards, Tudor times remain urgently, irresistibly alive to us?

Part of the explanation must surely lie in the fact that we’re dealing with formidable personalities. A couple of years ago, dramatist Kate Hennig showed her awareness of this in her debut play, The Last Wife, which received a sterling production last season at Ottawa’s Great Canadian Theatre Company. It focussed on Catherine Parr, Henry Vlll’s last Queen and a lady who — given the history of her predecessors — showed an impressive capacity for survival. Hennig’s evocation of the dying days of a tyrant’s reign was aflame with dramatic tension, but it was the play’s status as a richly realized character piece that gave it the momentum it needed. And it compelled us to give our full attention to the complex personalities of the key players — not just Henry and Catherine, but also Henry’s two very bright but psychologically different daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, as well as that shady but charming opportunist Thomas Seymour who would marry the widowed Catherine and also pursue some kind of relationship with the young Elizabeth, a relationship whose very nature has kept us guessing for centuries.

It’s that relationship that supplies the dramatic fuel for The Virgin Trial, the second instalment in Hennig’s Tudor saga. The new play has taken up summer residence at the Stratford Festival’s intimate Studio Theatre and once again reveals the playwright’s gift for psychologically astute characterizations and compelling dialogue garnished with moments of genuine wit. As was the case with its predecessor, it’s done in modern dress. Elizabeth is Bess, Lord Protector Edward Seymour is Ted, brother Thomas Seymour is Thom, and Mary Tudor is — well — Mary. It would be unfair simply to label this approach as gimmickry: indeed it brings into bold relief issues that have never really gone away, issues having to deal with the elusive dynamics of personal relationships and how they can affect a wider world of power politics.

Whereas the bulk of today’s thriving Tudor industry focuses on two aspects — Henry Vlll and his six wives being one, and the reign of Elizabeth the other — Hennig chooses to examine an aspect of Elizabeth’s life that often doesn’t get the attention it deserves. It has to do with the unrest and skullduggery following the death of Henry and during the reign of the boy king, Edward Vl. It was a time when Elizabeth, in danger for her life, was largely dependent on the dubious mercies of the state for her survival. Historian Margaret Irwin, author of a now forgotten and unjustly neglected cycle of novels dealing with this period, was fascinated with these years — indeed, one of these novels was appropriately entitled Elizabeth, Captive Princess. Hennig is on similar ground here although somewhat more audacious in her theorizing: whereas Irwin’s novels probably constituted G-rated history, Hennig’s reimagining of the Elizabeth mythology is prepared to enter R-rated territory.

It’s the teen-age Bess we’re getting here, a precocious 15-year-old suspected of treason because of her relationship to Thom Seymour, widowed husband to her stepmother, Catherine Parr, and also — some

might say — her lover. The bulk of the play consists of Bess undergoing interrogation by the authorities over the true nature of her relationship with Thom, who is now imprisoned in the Tower, and her possible complicity in the latter’s plot to seize the throne for himself. These scenes are interspersed with flashback sequences and also moments depicting the torture of suspected conspirators.

This is heady dramatic stuff — or at least it should be — served up in a script with all the potential for an exciting and provocative theatrical experience. But although Alan Dilworth’s production does maintain a momentum of sorts, it’s rather stolid and unenterprising in nature, and seems more interested in surface emotions than nuance.

Stratford’s Studio Theatre can be deceptive. The auditorium is tiny, but the stage is actually a good, serviceable size. But how well have Dilworth and designer Yannik Larivee acknowledged its possibilities? Even the scene changes seem clunky. There are a few simple props in the foreground and at the rear there is a scrim through which we see various methods of torture being applied — including, would you believe, Guantanamo-style waterboarding. Some might see the torture sequences as gratuitous and exploitive — but really, apart from seeming mannered in execution, the chief impression they leave is one of growing artificiality and monotony.

And what of the performances? A close-cropped Yanna McIntosh exudes an icy menace as the chief interrogator — Eleanor by name. Nigel Bennett seems a little too mild and ingratiating in the role of Ned — a.k.a. Lord Protector Edward Seymour, brother of the imprisoned Thom — and we need more glimpses of the determined opportunist indulging his own bloody-minded lust for power.

Then there’s Brad Hodder, swaggering his way through the role of Thom in the manner of someone who has just exited the latest trendy coffee bar. Hodder has a natural exuberance that suits the character and he deftly bridges the latter’s transition to defeat and desperation. But although his presence certainly makes an essential contribution to the play’s preoccupation with Elizabeth’s virginity (or possibly her loss of it) this version of Thom Seymour doesn’t convey much of the charisma of the historical figure, a man with a reputation in Tudor times of being irresistible to women. In brief, where is Stewart Granger when we need him? Furthermore, are we really seeing that much chemistry in his scenes with Bahia Watson’s Bess?

As for Watson, she can be a captivating presence on stage, and a key fascination of Hennig’s play comes from those moments when the sharp-witted young Elizabeth employs all her teen-age wiles to confound her interrogators and save her skin. These passages are reminiscent of some of the finest moments of Robert Bolt’s A Man For All Seasons, when Sir Thomas More confronts those who seek to destroy him, but is their potential fully realized at Stratford? Elizabeth l was a strong ruler but an enigmatic figure, and it is the enigma that tantalizes in the text of this play. Was this 15-year-old princess a total innocent in the scandal surrounding Thom Seymour? Or was she complicit? And what was the true nature of her relationship with him? Was it just an affectionate flirtation, or something more?

The text suggests a complexly drawn characterization, so Watson needs to allow the role to breathe. That means slowing down instead of being allowed to carry on at some moments like a shrill chatterbox whose speeches sometimes degenerate into garble. There’s a substantial performance lurking here — it just needs the right kind of release.

That leaves Sara Farb as Mary Tudor. This is the future Bloody Mary: wise to the ways of the world, sardonic in her wit, privately seething over the treatment of her mother Katherine of Aragon, Henry’s first wife, quietly biding her time as she draws nearer to the throne, and engaged in an edgy relationship with her half-sister, Bess. Farb’s detailed and knowing portrayal of Mary is the best of the evening, and her scenes with Bahia Watson’s Elizabeth the most fascinating. It’s with moments like these that you realize the full power of Hennig’s play.

(The Virgin Trial continues to Sept. 23. Further information at 1 800 567 1600 or stratfordfestival.ca)