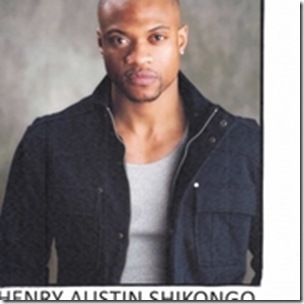

The Theatrical Journey of Henry Shikongo

Photo by Andrew Alexander

By Jane Baldwin

On May 24, I attended the première of The Boston Abolitionists Project at the Loeb Theatre in Cambridge, MA. This performance is one of several combined theatrical and scholarly undertakings, commissioned by the Civil War Project to observe the 150th anniversary of that singular event in U.S. history. It was also the final production of the graduating class of the American Repertory Theatre (A.R.T.) Institute for Advanced Theatre Training. Among the many talented students was Ottawa’s Henry Shikongo, remembered for his roles in, among others, the musical Blood Brothers and the poetic Under Milk Wood, the latter an award-winning production shown at the Shenkman Centre in Orleans.

In The Boston Abolitionists, a devised piece, created by the graduating students and director Steven Bogart, Shikongo played two major roles: Jonathan, a fictional character and the historical Anthony Burns, a runaway slave, captured, tried, convicted, and returned to Virginia under the infamous Fugitive Slave Act. Both had distinct personalities and mannerisms. Anthony Burns, depressed, frightened, angry, and largely silent was particularly notable for Shikongo’s physicality, a distinguishing feature of his Ottawa stage appearances as well.

A graduate of the Ottawa Theatre School, where movement is a strong element of the curriculum, Shikongo came to the A.R.T. Institute to expand and deepen his formation as an actor and earn an MFA. His attraction to the U.S. and admiration of Method-trained actors like Al Pacino and Robert De Niro were also factors. As a kid growing up in Ottawa, he often watched Inside the Actors Studio and thus was initially drawn to the Actors Studio Drama School at Pace University. A.R.T.’s Institute, on the other hand, follows a more classical, yet diversified, and even bicultural route. It is an offshoot of the well-known American Repertory Theatre Company, and is loosely connected to Harvard University. The most unusual aspect of the Institute’s training is its relationship to the Moscow Art Theatre (MXAT), Stanislavsky’s theatrical home.

Entering students plunge immediately into the Stanislavsky system through studying with a group of Russian visiting faculty from the MXAT School. Roughly half a year later, the students reprise their Russian training at MXAT during a three-month stay in Moscow. For Henry Shikongo, this experience was perhaps the most influential of an exciting two years at the A.R.T. Institute. He enjoyed the exposure to Russian culture and practicing the language, which the students take in preparation for their stay abroad. Most importantly for the young actor, through attending Russian productions and his studies at the MXAT School under Russian master teachers, he was exposed to an acting style or styles unlike those usually found in North America – certainly very different from the naturalism of the Method. He is very appreciative of the opportunity afforded him to work with those who have managed to keep Russian traditions alive.

In Moscow, the class performed their first play as A.R.T. students. Before leaving for their Russian residence, the class rehearsed what is called the “Moscow Project,” which functions as a rite of passage. Each year, the first year students prepare a production in Cambridge to be shown just after their arrival in Moscow. Shikongo’s class worked up a musical version of Molière’s The Imaginary Invalid, which played to acclaim at the MXAT School’s theatre. So impressed was Anatoly Smeliansky, the MXAT School’s director, that he sent the show off to play at theatre festivals in several of the ring cities around Moscow. Shikongo remembers the experience as a love fest between actors and public. (Russians take the theatre very seriously.) After each performance, excited audience members engaged the actors in conversation about the meaning of the play and production. Molière as an American musical was certainly a novelty for them, but one which they evidently enjoyed a great deal.

Back in Cambridge the next fall, the students elaborate on the differing acting styles acquired during their first year, but in a more practical fashion. While movement, dance, voice, speech, singing, and scene study remain vital, they are supplemented by Institute productions staged by faculty or visiting directors. As the year continues, there is a greater sense of urgency; the amount of work and its variety increases. In the spring, they take a three-week Shakespeare workshop with the nationally acclaimed director/teacher David Hammond, prepare for their New York and Los Angeles showcase, and rehearse their final play. While all these projects are intense and meaningful, the showcase, where they confront the professional world with all its opportunities and risks, is doubtless the most thrilling and frightening.

Several Los Angeles agents expressed an interest in Shikongo, requesting that he follow up with an audition tape, which has affected the way he thinks about the immediate future. He is literally pulled in several directions: Ottawa, Toronto, Montreal, New York, California, especially Los Angeles. Living in Los Angeles would offer more film audition possibilities, while an internship at the Actors’ Studio would teach him more about the Method. A strong believer in training, Shikongo has considered studying the Lecoq mime technique at the Dell’Arte School in Blue Lake, California. And, of course, Canada’s theatre draws him homeward. In an ideal world, all these possibilities would be available to him. As he puts it, “I just like to focus on the work and continue on my path to become a better actor.” Given Shikongo’s talent, determination, and love of acting, his ambitions may well be realized.