Stratford Embraces the Supernatural in Macbeth

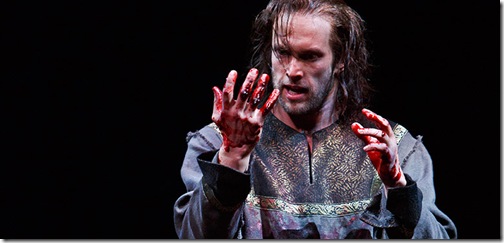

Photo: David Hou. Ian Lake as Macbeth

Macbeth directed by Antoni Cimolino

The supernatural is eerily alive and well in the Stratford Festival’s new production of Macbeth. But those who submit to its allure are fallibly, destructively human.

In our own age, this youthful Macbeth and his lady would probably worship social media and be dangerously susceptible to its excesses and its mistruths. Stratford’s revival may be very much in period, but a similar dynamic can still apply, even in 11th Century Scotland. This Macbeth may be a hero on the battlefield but he’s also a product of his times. In his world, ghoulies and ghosties and long legged beasties and things that go bump in the night are not an unnatural phenomenon. So, if he is dangerously ambitious, why shouldn’t he prepared to listen to the Weird Sisters and heed their prophecies of a great future for him?

This is a production shrouded in darkness. It also demonstrates the wondrous possibilities that the Festival Theatre’s famous stage holds for those who use it imaginatively. You look at those skeletal trees struggling to be seen in the surrounding blackness of the performing area, and you’re uneasily aware of an indefinable void. But set designer Julie Fox and lighting designer Michael Walton go further: this a darkness which threatens to reach further and engulf us.

So Antoni Cimolino’s production accepts the reality of apparitions in this 11th Century world — or rather their reality as they take shape through Macbeth’s own bloodshot prism. So in this production, when the Weird Sisters — portrayed here with spooky, malevolent conviction by Brigit Wilson, Lanise Antoine Shelley and Deirdre Gillard-Rowlings — materialize and start playing mind games with Macbeth, we can’t easily be dismissive of what we’re seeing.

Yet, Cimolino does bring a modern sensibility to a difficult play that has often defeated directors, even very good ones, who have done it at Stratford. Hence the production seethes with a noirish atmosphere that seems eminently appropriate for the doomed conspirators of Shakespeare’s brooding tragedy. Even Steven Page’s music and Thomas Ryder Payne’s sound design tremble with menace.

And in the Macbeth of Ian Lake and the Lady Macbeth of Krystin Pellerin, we have a couple possessed by darkness, a darkness intensified by their passion for each other. They are also young and unthinking. Macbeth may be a hero in battle but here he’s no mature seasoned soldier. Instead Lake offers us the sort of delinquent thug who delights in playing with fire and then discovers he can’t stop, even though it sets him on a spiral to disaster. Even in the countdown to the murder of Duncan, who has had the misfortune of accepting Macbeth’s hospitality, Lake conveys the ingrained arrogance and sense of entitlement that will justify his murder of the old king who loves him.

This a coarsened, sophomoric Macbeth, one who is susceptible to the witches telling him what he wants to hear — that he is destined to be king — but who also becomes a victim of increasing paranoia. The scene when the ghost of the murdered Banquo shows up at the banquet table is powerfully done, showing how this Macbeth can move from lofty victor to terror-stricken submissive in mere seconds.

It could be argued that a Macbeth this lumpish would be incapable of those more profound moments of soliloquy, but in Shakespeare even villains have their moments of philosophical reflection — and Lake delivers the “Out out brief candle” speech with quiet, shattering conviction.

Then there is Lady Macbeth. Krystin Pellerin is phenomenal — the Bonnie Parker to Lake’s Clyde Barrow. The sweet, honey-tongued girlishness of her early scenes is deceptive — dangerously so. And the by time Duncan dies, we know that we’re in the presence of someone lethal. The sexual chemistry between Lake’s Macbeth and Pellerin’s Lady Macbeth is there in spades, but it’s driven by an obsessiveness that is pathological. When Pellerin finally reaches the sleepwalking scene that can trip up many a good actress, we encounter an unexpected take on mental disintegration. The hysterical, defenceless child has taken possession of this once terrifying schemer; the moment is riveting and also profoundly unsettling.

This moves with the velocity of a bullet. It’s visually powerful and narratively clear. The cast is responsive to the demands of Shakespeare’s text. Cimolino also ensures a succession of engrossing set-piece moments. The sword battles, staged by the reliable John Stead, are fierce, bloody, and convincing. In a production high in ensemble quality, solid individual characterizations do emerge: Joseph Ziegler’s Duncan, sweet-natured and vulnerable; Michael Blake’s bereaved Macduff, his integrity intact even in his quest for vengeance; Antoine Yared’s Malcolm, very good as a self-doubting candidate for kingship; Scott Wentworth’s Banquo, a most persuasive ghost; Cyrus Lane whose garrulous porter provides comic relief in a show that probably needs it.

There are times when evil seems to be seeping into the very fabric of this production. There is no more terrifying moment than the murder of Lady Macduff and her son (a pair of heartbreaking performances from Sarah Afful and Oliver Neudorf) by Macbeth’s goons. At this point, it’s as though the cosmos is being ripped asunder — and, of course that danger was always on Shakespeare’s Elizabethan mind.

So here’s the bottom line. Stratford’s history is punctured by a number of failed Macbeths. This is one of the triumphs.

(Macbeth continues to Oct. 23. Ticket information at 1 800 567 1600 or stratfordfestival.ca)