Mies Julie in the Karoo: a stunning metaphore captures the difficult transformation to Post Apartheid society

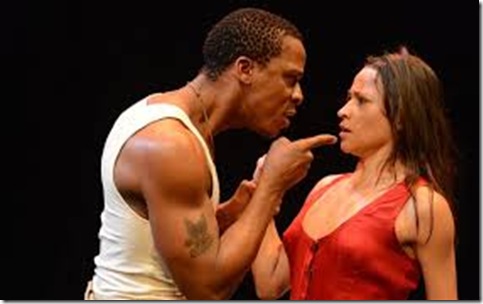

Photo:Telegraph.co.uk Bongile Mantsai and Hilda Cronje.

Yael Farber is an extraordinary artist of the stage! Recognizing how Strindberg’s Miss Julie has established a brilliant framework for all forms of power relations, Farber transforms the play into a metaphor of contemporary post-apartheid South Africa where class, land rights, sexual tension, ethnic, social, political and cultural differences clash head on in a context of raging anger and lust, setting the background for a drama of tragic self-destruction.

The site of Farber’s version of the play, is the kitchen of a Boer homestead, located in the desert region of Karoo, where generations of racial and class struggle have not yet come to an end , in spite of the new political situation in the country. On this farm, where Julie (Hilda Cronje) lives with her father, the master of this land, she and John (Bongile Mantsai) the son of the master’s housekeeper, perform an intense and sexually charged death ritual which tears apart any form of “truth and reconciliation” that one might hope for.

Julie wanders into the kitchen, from an outdoor party, where the singing and percussions tell us that things are heating up in the crowd of revelers, descendants of the originally dispossessed Africans still working the land and now celebrating 20 years of freedom after the end of Apartheid. An ongoing ritual of social transformation is in progress and this sets the action in a liminal space where laws no longer apply, all tabous can be broken, all habitual behaviours can change, temporarily at least. The fact that the Master is absent makes it all the more exciting, and in fact, all is about to break down.

A bored Miss Julie, annoyed, slightly drunk, swings into the kitchen exhibiting her dancers body as she flits about, throwing searing glances over to the young man shining her father’s boots in the corner. Her movements are flawless, almost animal-like. She throws itself on the table or on the ground in this all too familiar kitchen, where she is drawn especially today, because there is a party out back, her father is not around and she can mix with the workers. She aggressively goes after young John polishing her father’s boots in the corner. Provoking him, revealing her legs, enticing him to touch her and then pulling away brutally. Thus begins the sensual mating ritual of two bodies attracted to each other, sending out signals of a physical language even more powerful and more meaningful than the spoken word.

John avoids her gaze, he hesitates, follows her with his eyes, never daring to catch her gaze. Those looks, the slightest turn of his head and her taunting dance, tell us there is a history of something between them, a history that is built of repression, desire, punishment, cruelty, of lack, and it all simmers through those taught, sweat soaked bodies, that have emerged from the life of dry isolation in that the desert of Karoo. Farber’s staging is as much a choreography as a direction of actors and it all comes together most beautifully. Alcohol flows, the music vibrates, the percussions rumble, the presence of this young Kaffir, far beneath her station, excites Mies Julie. She wants him to come out and dance with her. His body stiffens, he knows he mustn’t but suddenly he draws on his gumboots, leaps over the table and flies out into the dark outdoors where he unleashes his body into a sensual gumboot dance that becomes his moment of physical and sexual liberation. Then both of them disappear into the night. At that moment, Mantsai becomes the central force of a frantic competition where each participant tries to impose his or her own physical energy on the other. For a short moment, John is not the oppressed one and yet Mies Julie persists with her advances. Then suddenly he isn’t playing any more. “I’m only a man” he mutters and then begins a most violent sexual encounter, perhaps at the limit of a rape, that is so wildly physical, one wonders how the actors managed to unleash such energy without losing their cool. In that crazed moment on the table everything suddenly changes,. The masks come off, the games stop and the various stages of truth pour forth. He is in charge now. The tables have turned. All those years of repression explode in both of them. Can they run away together? Can they make a new life in this new South Africa? Such intellectual questions filter through the physical performances as Yael Farber’s shows us how corporeal theatre can illustrate the most complex levels of human relations in a perfectly clear way. .

The arrival of housekeeper Christine (Zoleka Helesi) John’s mother, sends the encounter on a new direction: accusations, rage, tortured memories of the pass mix with the loss of ancestors. The play foregrounds the deep psychic damage that apartheid has done to these human beings and the scars it has left on their capacity to communicate. It quickly explodes into a furious dance of accusations and pathetic pleading , of raw sexual desire and unlawful emotions as John blurts out, collapsing with helplessness: : “our love is not possible in this mess”. as they try to calculate who really are the masters of the country. Julie has lost her identity! She no longer knows where to go or where she belongs. The deeds to the land are no longer enough to ensure her right to the land as long as John’s ancestors, buried in the earth below keep an eye on the place. Christine in her despair, is constantly on her knees, keeping an eye on the burial place under the floor, and eventually washing away the blood of the last hope of reconciliation as her son puts on the boots he has been polishing and declares he will imitate the master.

Speaking in Xhosa and Afrikaans with her son, Zoleka Helesi, in traditional dress, cuts a strong household figure, constantly adressing her absent ancestors. Singer, Thandiwe Nofirst Lungisa, against a background of Xhosa music, performs her songs with a deep throaty voice that vibrates in her chest, calling up her fore fathers, another archetypal matriarch whose anger takes on Epic proportions. All these figures are epic creations that symbolise the past still haunting this troubled universe, where their rituals unfold and carry the young people along their path of doom.

The performances were spell binding. Mantsai is a trained dancer and Hilda says she is an actor “who moves” but their bodies create the impression of a truly transformative experience over which they have almost no control. As the mist blows in and engulfs them, they emerge and follow their instincts to that tragic conclusion, showing how all hope for the new state is gone. As for the theatre, politics has found its ultimate expression in this exciting stage event where Yael Farber has shown how theatre can engage and even physically possess the most sceptical of spectators. And isn’t this really what theatre is all about?

Mies Julie plays in Montreal until May 3. Performances are at 8pm in the Cinquième Salle of the Place des Arts., Call La Place des Arts at 1 514-842-2112. The show is in English with some bits in Afrikaans and Xhosa . There are French surtitles. It then moves on to Toronto.A Production of the Baxter Theatre Centre and the University of Cape Town,in association with South African State Theatre

Mies Julie

Text and direction by Yaël Farber. Inspired by the play by August Strindberg

Music: Daniel and Matthew Pencer

Musicians: Brydon Bolton, Mark Fransman

Set and lighting: Patrick Curtis

Cast:

Bongile Mantsai John

Julie Hilda Cronje

Christine Zoleka Holesi

Singer Tandiwe Nofirst

A Production of the Baxter Theatre Centre and the University of Cape Town

in association with South African State Theatre