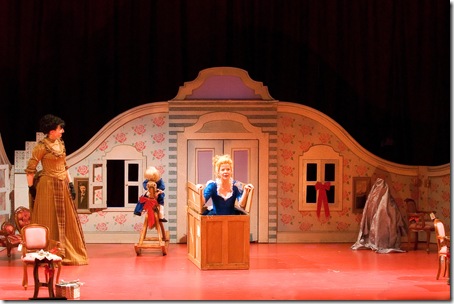

Mabou Mines’ DollHouse: at the Cutler Majestic in Boston, MA

L.to R. Janet Girardeau, Maude Mitchell

After nine years on the road, Mabou Mines’ DollHouse, conceived and directed by Lee Breuer, arrived in Boston on November 1. The week’s run at the Cutler Majestic brought this marathon tour to an end. As a fan both of Ibsen and cutting edge theatre, I had been looking forward to the event with great anticipation.

For the most part this “concept” version of the play lived up to my expectations. Unlike other stylized Doll Houses, which look for relevance by contemporizing the play – such as German director Thomas Ostermeier’s 2002 production in which the Helmers live in a chic modernist apartment and Dr. Rank suffers from AIDS – the world of Breuer’s Nora is fixed in the late nineteenth century. From her blonde bouffant hairstyle to her blue bustled dress, Nora looks the picture of her time as she munches her macaroons, confides in Kristine Linde, and flirts with Dr. Rank.

Realism ends there. Breuer, faithful to Ibsen’s script (in a new translation) and perhaps even to his spirit – given that the production revolves around the struggle for power – offers the audience a visual metaphor that dominates it. All the female characters are at least six feet tall, while the males are considerably less than five feet. The metaphor elicits several questions, chiefly: Is Torvald Helmer Nora’s doll or she his, as is traditionally the case?

Nora still plays the little squirrel – scurrying about wagging her bustle like a tail – yet picks up Torvald, as for example, when she places him on a table at a moment when she needs his protection. From time to time, to deemphasize the size difference, Nora kneels in her scenes with Torvald, which would seem to equalize them, but actually places her in a supplicant role.

To underline the production’s theatricality, it opens on an almost bare stage with crates scattered around. A young woman, carrying a musical score, walks on and sits at the downstage piano, her back to the audience and begins to play. Red velvet drapes drop down forming the shape of a room. Red wrapped Christmas presents are brought on. A cardboard doll house – a structure so small that the women have to crawl through the doorway – is assembled within the framework of the draperies. The miniature furniture is comfortable for the men who fit in this world, while the women have to twist themselves into unnatural shapes.

The play, divided into two acts, is parodic in the first, a sometimes clumsy device. Nora’s chirpy, high-pitched voice, complete with a mock Norwegian accent, makes her difficult to understand. Other stratagems are more successful. Songs are interspersed as when Torvald, Dr. Rank, and the maid perform a ditty about the squandering skylark. And while music plays an important role, the acting emphasis in this production is essentially corporeal. Nora’s highly rehearsed performance of the model nineteenth-century wife is demonstrated as she spins like a doll in a music box. Her secretiveness evinced when she pulls a macaroon out of the head of a doll dressed and coiffed as Nora’s double.

The acting style is melodramatic, with music – largely Grieg’s – played throughout, as in a silent movie. Confessional speeches are frequently aimed directly at the audience with the actor spotlighted. The melodrama is further heightened by the addition of silent nightmare scenes, which also add an element of expressionism. With a bow to the nineteenth-century Freud, they feature a gigantic, all-powerful witch-like woman.

The mood changes in the second half as Nora gives up her dream of self-sacrifice for her “heroic” husband. The danger threatening her is not only Krogstad, but also Torvald who, in this performance, comes close to raping her upon the couple’s return from the party. When Nora ultimately confronts Torvald, it is from a box in the theatre emphasizing both the distance between them and the production’s metatheatricality. Still on stage, Torvald moves towards Nora, looking up at her. Their speeches become arias and the scene an opera watched by miniscule marionette couples seated in rows of boxes upstage. As Nora sings her dialogue, a panel of her white dress unfolds and drops down towards the audience, while she simultaneously reaches up and removes a blond wig. Before the audience can fully absorb the shock of her shaved head, she strips off her clothing, revealing a slender, almost androgynous body. Her femininity (even her femaleness) disappears with its outward signs of dress and hair. The grandiose gesture can be read as both the death of and the rebirth of Nora.

The lights on her fade; Torvald descends from the stage and staggers down the aisle, plaintively calling her. As he reaches the auditorium’s doors, there are two sudden crashes. “The door slam heard round the world” is more ambiguous here. The play ends with the appearance of the Helmers’ daughter alone on stage, which raises further questions about the future of women.

On the whole, DollHouse was well acted. Maude Mitchell was excellent at playing the multiple facets of the deconstructed Nora. On the evening I saw it Kristopher Medina commendably covered for the production’s usual Torvald.

While this was an incredible theatrical experience, foreknowledge of the text was a necessity even to follow the plot and characters.

Mabou Mines

DollHouse

Adapted from Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House by Lee Breuer and Maude Mitchell

Conceived and Directed by Lee Breuer

Original Music and Collage of Edvard Grieg’s Piano Works Assembled by

Eve Beglarian

Set Design – Narelle Sissons

Lighting Design – Mary Louise Geiger

Costume Design – Meganne George

Puppetry Design – Jane Catherine Shaw

Sound Design – Edward Cosla

Choreography – Eamonn Farrell

Additional Choreography – Erik Liberman

Cast

Nora Helmer – Maude Mitchell

Torvald Helmer – Kristopher Medina

Nils Krogstad – Nic Novicki

Kristine Linde – Janet Girardeau

Dr. Rank – Joey Gnoffo

Helene – Jessica Weinstein

Emmy Helmer – Hannah Kritzeck

Piano Accompaniment – Susan Tang