Jane Eyre: an adaptation of the novel that translates verbal description into spacial artistry”

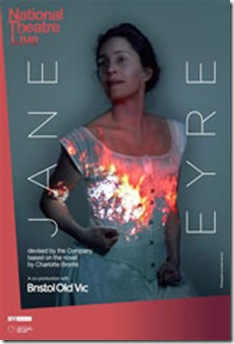

Photo from the site of Front Row Centre.

The National Theatre of London’s adaptation of Bronte’s novel Jane Eyre that reached us live by satellite recently was the result of a collective effort on the part of all the actors, so we were told during interviews conducted during the intermission. Ultimately, it was Sally Cookson who imposed the final directorial choices, intent on emphasizing the strength of this legendary heroine, who survived çruel treatment at the hands of her “step” family .

The play opens with the birth of little Jane who is passed on to her Aunt upon the death of her uncle and from that point on, much attention is focussed on the aggression and meanness to which she was subjected as a young girl. Madeleine Worrall as Jane Eyre in this early portion of the play purses her lips, squints, tightens her facial muscles and shows us what a tough little creature she is becoming as she swallows the insults, the taunting, and vicious behaviour of her cousins and aunt who toss her off though she were some filthy Cinderella. The fable becomes an adult horror story that allows our heroine to rise out of the emotional rubble and establish her own strong presence as a mature woman.

This physically vibrant version of Bronte’s novel , transforms description into movement and spatial manoeuvering as director Sally Cookson’s breathless choreography has the actors rushing across portions of Michael Vale’ s constructivist influenced set, climbing ladders , running up and down various platforms, slipping into the shadows of the lower spaces that appear under the open floors of the different areas of the scenography, and collapsing exhausted in a heap. At one point, Jane even climbs up over the imaginary roof and the illusion of her possibly jumping off the third floor in despair, is almost perfect, thanks to the lighting and the movement of the stage that slowly lowers the whole set as the body of the actress is elevated into the sky.

This is an excellent illustration of the way a work of literature is transformed by the conventions of the stage. Some narrative details are eliminated but new elements introduce new contemporary meaning such as the on stage musicians, thrust to the back of the set, hidden in the shadows, adding various beats, percussion instruments, jazz, contemporary mood music and well as lyrical and even operatic moments, whenever the atmosphere requires such sounds. Take for example the scenes where Jane drives away in a horse drawn carriage as the percussion beats out the hooves of the animals while the actors jump like galloping horses to create a feel of speed and desperation, creating a concrete sense of fear tapped out by the rhythmic excitement that intervenes at the right moments. The play appears, in fact to be conceived more as a film scenario than as a written work because of its oral and physical components that move us away from the novel and take over the stage at various moments of the production.

Later, as the mature Jane arrives at the home of the strangely elusive and uncomfortably brooding Mr. Rochester, the tone shifts, the rhythms change, darkness descends on the set, the members of the household appear on that long ramp, barely moving, until Rochester (Felix Hayes) makes his appearance, something like the seductive but brooding demonic romantic hero who appears out of nowhere to question this new woman who has come into his household and upset its rhythm. But here, new rhythms appear. His household is occupied by disturbed people, his young ward comes flitting around in fits of nervous hysteria and strange screaming and laughing sounds echo through the halls as the servants cringe in silence in the background. The soundscape takes on a particularly important meaning here as Rochester’s feelings for Jane develop and his terrible secret which he does not dare to explain, is finally revealed . That was a great moment of acting that turned this strange and secretive individual into a deeply suffering human being.

Bertha Mason the Jamaican wife, an unusual representation of the legendary “Madwoman who is kept locked in the attic,” , suddenly becomes an uncanny and overwhelming presence as her strong soprano voice projects the heightened emotions of a creature from another performance mode. She emerges as the distraught heroine of an opera with the atonal sounds of a Benjamin Britten composition, ready to kill or die for her love. This alienates her from the others but it also indicates how the stage took advantage of her physical presence by giving her a beautiful voice in order to make us understand how she overwhelmed Rochester and was able to charm him as a young man.

However apart from Melanie Marshal’s singing, the other leading roles are all spoken. Rochester and Jane’s final union becomes a most passionate moment that almost obliterates the physicality of the earlier parts of the performance and even corresponds to the blazing ending that destroys Rochester’s dwelling. In that sense most of the important narrative moments in the book are represented in some way by this adaptation but because this is not a naturalistic stage esthetic, most of the elements of the set became signs of what churns around deeply within the psyche of these creatures . Even when they were rushing around and physically over exerting themselves , this use of the body became the expression of underlying impulses that revealed more than one might want to admit. That was a most interesting thing about this staging. .

Recently at the University of Ottawa, André Perrier attempted a similar exercise with Les Reines, an interesting adaptation of several Shakespearean plays by Quebec playwright Normand Chaurette . His rereading of Richard III among other texts, featured the female characters of the royal household of the dying King Edward IV and the family of the Duchess of York who were all stunned by fear, anger, hate and ambition before the very real prospect of changes in family power relations about to take place when Edward finally died. Director Perrier stated in the programme that the play was an example of his research on the acting process where his characters had to depend on purely physical forms of expression to reveal their psychic impulses . Almost all naturalistic expression was therefore denaturalised in his biomechanical actors except for one character who became the symbol of the “victim”, which could have been read as a stereo type in such a feminist play, although the young actress presented it in such a way that highlighted the language and moved us deeply. Nevertheless, . Perrier did not quite succeed in his case but Sally Cookson from the National Theatre succeeded beautifully because her choices allowed her characters the freedom to evolve according to their emotional needs that pure physicality did not quite fulfill as they matured. The result was a truly exceptional scenario set out for the stage, one that did not betray the novel , but rather enhanced its possibilities.

Alvina Ruprecht

Ottawa. December 17, 2015