In the Unseen World: Performing storytelling in the world of indigenous peoples

In the new theatre research LabO located in the Ottawa Art Gallery, a group of students and friends came to watch the final portion of a research project presented by indigenous artists collaborating with Vivi Sorensen, free lance artist who is preparing her directors diploma for the Masters program in Fine Arts at the University of Ottawa. Sorensen, an Inuk actress from Nuuk , the capital of Groenland, and a graduate of the Danish School of Performing arts , has integrated Myths from the northern peoples into her storytelling techniques .

Working with her is Mitali Buscemi who grew up in Nunavut. She has worked with the Stratford Theatre Festival, is fluent in Inuktitut , the main northern language, and has performed in film and theatre. We also met Will Lafrance, who comes from the Algonquin region of Ontario, who is not fluent in Cree from his region but he has had a sound professional career in English in theatre and in film .

Flanked by her talented collaborators filled with memories and teachings of their traditional stories , Vivi Sorrensen set off to create a collective storytelling event based on a connecting theme: The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Because it touches on such a sensitive question which has caused much alarm and sorrow throughout the whole indigenous community as well as all of Canada, we assumed the performance would be an attempt to understand why these murders have never been solved and how it is that these killers are still at large.

The material is vast and the presentational forms of the storytelling styles are just as varied, given the mixed cultural origins of all these performers and the traditional sources that have inspired these young people who are both storytellers and actors. That might explain our disappointment when we realized that there seems to have been a rupture between the artists intentions and the actual performance. No doubt, the performative exploration was extremely difficult because it included so many elements that had to be sifted out of issues that were so complex: family relations, narrative forms, traditional images that carried so much collective meaning.

This performance is not a detective style of investigation but a psychic examination of the state of mind of these women faced with the horror of death that apparently they could not avoid. What prevailed then was less the content than the different forms of storytelling that emerged during this encounter.

I could not help but think back to the event entitled Kiviuq’s Return, a collective work produced by Quaggiavuut from a Nunavut-based arts organization that has also worked in Banff with dancers, choreographers and technical staff from the northern areas. Singers, musicians, story tellers, dancers, actors, painters, set and costume designers, and all manner of artists interested in exploring the re-imagined journey of the legendary Kiviuq , the great northern figure who represents all life as he returns through the whole Arctic territory. Produced as an epic event at the NAC, it brought together a group that shared its artistic talents, spoken and sung mostly in Inuktitut. What we see in the LabO is perhaps of similar inspiration but a very different form of realization because it is not a finished product but the study of a process that includes peoples from all of Canada and beyond, not only the northern regions whose mythologies are similar among themselves but removed from those of the Europeans who inhabit the rest of the land.

It was soon very clear that the focus on creating an atmosphere, a world of the north, a place where traditional stories could blossom, moved beyond the theme of the murdered women which was apparently foregrounded in such a way that we hardly recognized what was being done.

The black box of the LabO here in the new Ottawa Art Gallery presented a flexible space which allowed stark lighting effects, a plastic screen that reflected the northern sky and drew the audience into the story tellers’ space as the actor pulled the sheet over our heads in an immersive theatre gesture. Thus we all found ourself physically integrated into the world of these actors who were trying to explain what they felt, based on their own particular storytelling traditions and personal lived experiences.

Each voice intervened in his or her own way, with his/her own language as a distraught woman or a Shamaanique figure wearing a mask, that created an important living presence communicating with the humans in that particular story.

In fact in the first few moments, Will Lafrance, or “Roger”, wonders which s tory he should foreground since there are so many of them . Always seeking the indigenous perspective drawn from the multitude of peoples represented in that space: half Inuk, or first nations or seeking out the conventions of each story where the individuals, the spirits, the animals transformed into humans all fit into this world where mythological animals fuse with human beings or , as we have seen in many of Thomson Highway’s plays, the appearance of Nanabush, the great shamaanique figure of the “Trickster” that transcends the human and the nonhuman, the visible and the invisible to create the link between both worlds where all will eventually meet. Will Lafrance became the black masked raven, the traditional Algonquin n(m)anabush who also appears in the Western peoples mythologies and rituals.

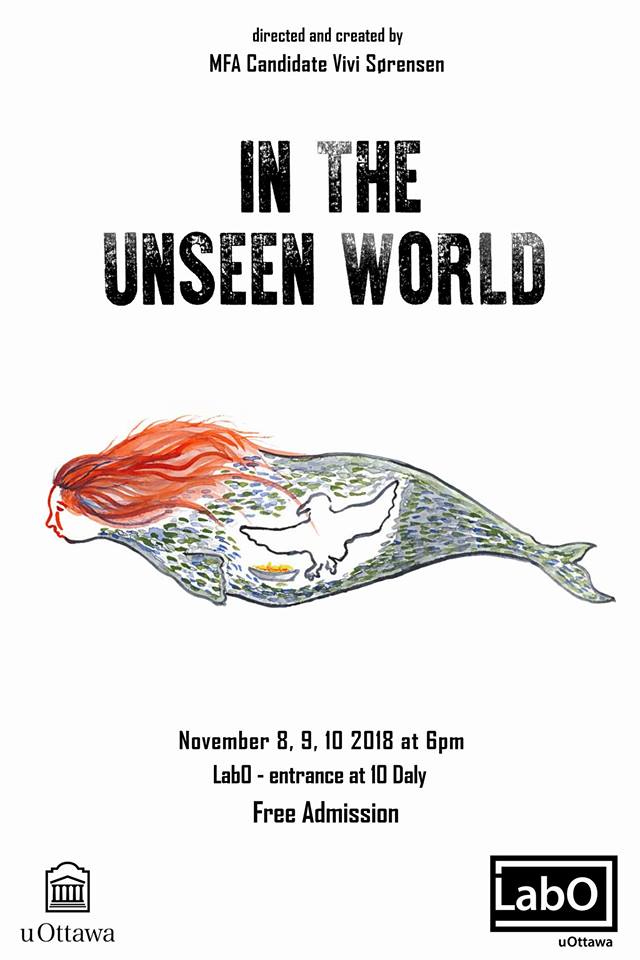

As for the murdered women, the questions were asked almost obliquely, fused with the traditional stories and suggested in the many texts that were spoken. The story of Nanabush from the Algonquin legend is united with the northern tale performed by an angry young woman on stage speaking to the raven in inuktikut. The story of the fishmonster and the myth of the Whale and its flaming soul where we find the young woman hiding deep in the interior of the Whale as combat flares up from inside its belly while the woman presides over the inner workings of the animal. Each actor takes on a different role as they all move about within their own tales and are transformed by the words and the appearance of each creature as humans and animals meet in a superior place where they all try to navigate.

The theatricality of the plastic screen and the harsh lighting that transformed the upper areas of the performance space propelled the lights around the audience creating the most striking effects. The lone speaking actor partly immersed us in the upper world of the unseen as she unfolded her plastic screen sheet, dragged it over our heads and brought us all together in that storytelling world. The voices were good, the interpretations were very strong and the LABO became, for a brief while, the site of an unseen world where we felt we were on the brink of some discovery but then none of this really told us what we hoped to learn. But then our expectations were different from those of the performers.

This work remains essentially an attempt to examine the different kinds of performative techniques that emerge from each of these founding stories. That is no doubt the most important part of the evening. They are not trying to resolve an issue, guided just as much by the expectations of the public as by the needs of the performers and that is the relationship that must be reconsidered if we and they want to move beyond the feeling that the artists are only speaking to themselves.

The sudden death at the end, left me with a multitude of questions. An exchange between the artists and the public should have taken place after each performance to enlighten an audience that had no narrative to grasp in this case but it would not have been necessary if all that light and shadow had projected meaning. On its own, the storytelling process did not lead us to a better understanding of the terrible events that had taken place and we are still wondering why.