Billon at the GCTC and Trottier at the Cube Gallery. An affinity for human cruelty and suffering.

Photo: Cube Gallery. Gerald Trottier “Dead Person”. Last night at the Cube Art Gallery, down the street from the Irving Greenberg Theatre Centre where I was planning on seeing the first preview of Butcher, there was a Vernissage of an exhibition by Canadian artist Gerald Trottier, entitled “Wounded Creatures of the Earth”. It is a series of watercolour and mixed media drawings, showing cruel images of human beings going through ritualized behaviour often related to Christian sacrifice, to revolution, to individual and collective suffering in the world, to poetic symbols of human figures torn apart, embedded in trees that evoke the crucifixion or human beings huddled together in distress or seeking warmth and comfort.

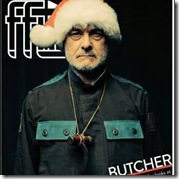

Photo John Koensgen. Down the street, Nicolas Billon’s play Butcher was opening an hour later the same evening, and it occurred to me that the Trottier exhibition was an excellent preparation for anyone intending to see Billon’s play. Trottier’s work, strongly influenced by images of Catholic based sacrifice, martyrdom and uplifting redemption played out by unidentifiable human figures, is very near the spirit of Billon’s play, which is more deeply anchored in the horrors of current history. Billon’s work identifies the monsters of our time and rapidly fits them into recent events which bombard us every day on television and radio. In other words, Trottier the visual artist is the unquestionable visionary whereas Billon, the playwright makes the links between ancient and contemporary political culture producing visual signs that are all recognizable.

The star pieces of Trottier’s exhibition were the bulging eyed and boney faces of the sick and terrified. Fearful faces gasping out silent screams, one peering out of a pyjama-like suit sending us back to the inmates of a KZ lager. The star characters of Butcher are four individuals central to a story where levels of realistic narrative are peeled away until the putrid essence of each of these beings is left to fill the stage with its nauseating smell. Keith Thomas’ sound design even suggests a depth of suffering far greater than reality could ever hope to do. Moments of Eric Coate’s directing and definitely the dramaturgy itself thankfully avoid slick voyeurism which could very well have been suggested by Roger Schultz’s ultra-realistic stage design of the police station.

You have already guessed that it is very difficult to discuss the play because no recognizable details of the performance can be revealed. There are however, impressions that have to be addressed. The first 20 minutes in the police station, where a mumbling, trembling apparently confused Josef Dzibrilovo (John Koensgen) has been dropped off, are at first surprising. Then the rhythm slows down. The detective (Sean Devine) tends to make silly jokes, do what he is told and behave like a foolish, mindless coward. Quickly we realize that this first impression is only a necessary prelude to what follows. Old Josef only speaks Lavinian, (remember the name of Titus Andronicus’ daughter who had her hands chopped off?). In the police station we also meet a young lawyer who understands the old man’s language. In comes an attractive young lady, the lavinian interpreter who will help them all understand what Josef is saying, and from that point, I must leave you to your own devices.

References do come to mind. The conflict takes us from tactics used on TV Police dramas that are not particularly original, through a theatrical patchwork of family vengeance (think of patricide, infanticide matricide and all the killings that structure Aeschylus` work The Oresteia) as well as the rivalries between religious factions currently taking place in Syria and elsewhere in the Middle East, cases of ethnic cleansing and genocide that have left a trail of horror on the human race . The conflict is spelled out near the end when the relationship between justice and vengeance are stated by a snarling killer who insists they are the same thing. That is the crux of the argument here. We are told that revenge and hate are languages much easier to justify than the search for justice because the general public finds it much more satisfying to refuse justice to a monster who has taken away a loved one.

The ending of the play however brought about much ambiguity. One of the characters refuses to be caught up in the circle of hate and vengeance that will emerge from this encounter and he yells: “that’s enough” . Thus it appears that the author gives his own answer to the question. Revenge must come to an end because we are civilised beings. However, the image of a certain young woman suddenly appears bathed in an unreal light, smiling in a beguiling way. That image completely reverses the impression one might have at that point. Is this a spectral presence satisfied with what has happened because she has had her revenge? Is it the image of a woman who suggests she will haunt them all until their dying day so their guilt will be with them for eternity and their suffering will never cease? It is at that point that the ambiguity built into this play becomes too clear. Billon is not trying to resolve the debate between vengeance and justice because the question cannot be resolved. He has found a perfectly powerful dramatic device on which to build all the necessary emotions because emotions are what grab audiences, not ideas (apparently) and Billon lets us know that very clearly. He has created a clever web where he snares us in a mixture of shock, and disgust, and fright, and fear, while evacuating any thoughts of justice, or civilised behaviour, or any conclusions that invite discussion. We are no longer in a theatre of ideas that was so popular in Europe during WWII. Thus the author avoids the need to commit himself to an answer and he gets away with it because we come out of the theatre nearly stunned! Nothing else seems to matter except the emotional experience. The play is a perfect work of emotional manipulation .

John Koensgen , who has played the role of Josef in three different productions since it was created in 2014 has mastered the expression of a language that no one understands but he makes it all crystal clear. His body language, his suffering face never appear overdone. Note as well Samantha Madley as the interpreter and Jonathan Koensgen as the Lavinian speaking lawyer called in to help discover who this strange old man could be. In the meantime, you might want to see the play to work out answers for yourself, that is if the subject matter attracts you and if tickets are still available.

Butcher by Nicolas Billon, plays at the Irving Greenberg Theatre Centre. It is a production of the Great Canadian Theatre Centre and the performance has already been extended for 7 more days

Butcher by Nicolas Billon

Directed by Eric Coates

Cast:

Josef John Koensgen

Hamilton Barnes Johnathan Koensgen

Detective Lamb Sean Devine

Elena Samantha Madely

Young girl Maggie Mojsej

Creative team:

Set and costumes: Rober Schultz

Lighting Darryl Bennett

Sound designer and composer Keith Thomas

Soudscape has been adapted from music originally commissioned by the Centaur Theatre

The Lavinian language was created by Christian Kramer and Dragana Obradovic