Lara Loves Leonard

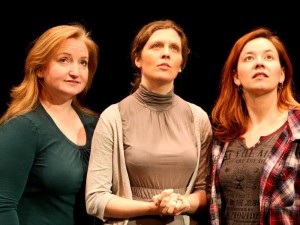

Lara Loves Leonard is a real gem at the 2015 Ottawa Fringe Festival. Lara MacMillan performs parts of Cohen’s poems and songs such an infectious passion that she elevates the already great artist’s work. Her interpretations of Cohen’s songs are emotional and sensually sultry. Her diction and pacing while reciting the artist’s poetry allow the words to seep into your very skin. MacMillan knows just how much time to give each word and each pause. She leaves you hanging on a word, desperate for her to continue, to fill you with the emotion she so readily shares through her craft and talent. Everything is so precise when it comes to MacMillan’s performance, from her diction to her movements.

She intersperses the songs and poetry with personal anecdotes of how a particular songs affected her. However, she maintains a balance between the three elements so the show, even though it’s just her standing on stage, never feels stilted or boring. It helps that MacMillan has such an expressive face and oozes charisma. This is a performer you want to get lost in; you want to be taken along on her journeys. This is a performance you wish didn’t have to end after only one hour.

For those who love Leonard Cohen, and for those who wish to be carried away and feel something extra, this is the show for you. Wonderfully put together with

Lara Loves Leonard plays at Studio Léonard Beaulne