Butcher tries to have it both ways!

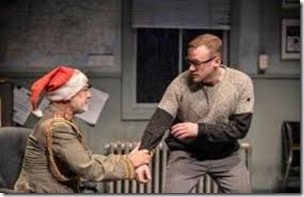

Photo: Andrew Alexander

One thing is certain about Canadian playwright Nicolas Billon. He is the slickest of theatrical tricksters.

Audiences attending his much-heralded new play, Butcher, now at the GCTC, may be assured that they’re in for a shocker of an ending, one that turns pretty much everything they’ve assumed beforehand upside down and inside out.

But can we also be convinced that Butcher is anything more substantial than a cynically crafted thriller that plays manipulative mind-games with the playgoer in the same way that it does with some of its characters? Can we really buy into the pretension that the horrors it depicts are essential to some deeper dramatic purpose that will engage our moral conscience and force us to think more deeply about the world we live in and the terrible things human beings do to each other?

The play seems in conflict with itself. It wants acceptance as a crackingly effective thriller — which, on some levels, it is. But it also wants to be taken seriously as some kind of profound artistic statement.

Eric Coates, a sensitive and discerning director, seems to have experienced difficulties reconciling these elements, given the uneasiness of the production currently selling out at GCTC. It’s easier to manage those early deceptive bits of light comedy than to find the right tone for the play’s later moments of dismaying violence. Because the script is cloaked in the garb of a thriller, thereby implying escapist entertainment, where is this brutality supposed to take us? Can it effectively dodge the indictment of being gratuitous and exploitive?

“It’s like a Tarantino movie!” one male playgoer was heard announcing to his girlfriend after the performance — and there’s the rub. Does anyone seriously believe that the credibility of a play like this can be bolstered if audience members are ready to relate it to Quentin Tarantino’s view of violence as some kind of spectator sport? One hopes not — although on opening night you were occasionally hearing titters of pleasure at the wrong moments.

Because of the surprise elements that Nicolas Billon has lined up, there are limits on what one can say about the play. At GCTC, designer Roger Schultz is giving us a very credible representation of a police station interior. It’s Christmas Eve, and the man in charge is the somewhat harassed Detective Lamb who would sooner be at home with the kids. Instead, he’s trying to deal with the crumpled remnant of a human being who has been mysteriously dumped on the precinct doorstep with a butcher’s hook around his neck. Josef Dzibrilovo — for that is his name — is now slumped on a chair, scarcely conscious, wearing a bedraggled Santa cap and an ill-fitting military uniform. When he speaks, which is infrequent, it is in an incomprehensible Slavic language that we’re told is “Lavinian” but which is actually a fictional creation prepared for the purpose of the play by a pair of University of Toronto academics.

This strange arrival is equipped with the business card of a Toronto lawyer named Hamilton Barnes who duly arrives, expressing mystification over why he’s there while still trying to co-operate. Next comes a female translator named Elena. Soon after this we discover that the aging Josef is minus his toenails and could have a sinister history. It’s time to let the bloody revelations pour forth and the acts of torture resume.

Butcher shows some indebtedness to the revenge tragedies prevalent in the Elizabethan and Jacobean drama of four centuries ago. It also becomes clear that this play is seeking to validate its preoccupation with blood and vengeance within the context of the Balkan wars of the 1990s, conflicts triggered by the renewal of centuries-old tribal hostilities nurtured by such unspeakable criminal atrocities as ethnic cleansing.

Indeed, the name assigned the bogus “Lavinian” language conjured up for us in the present play is clearly inspired by Shakespeare’s apprentice work, Titus Andronicus, and the character of Lavinia who in the course of that play is raped, has her hands cut off and her tongue ripped out. Butcher conjures up a retribution different from that dreamed up by Titus, who served up his chief tormenter a meat pie containing the baked remains of her two sons — but what transpires on the GCTC stage is ugly enough on its own count.

Whether Titus Andronicus offers genuine catharsis continues to be debated to this day. It is certainly present in The Oresteia, the Greek trilogy cited by Billon as an influence on his own work, but it’s at best nebulous in Butcher. Perhaps, of course, Billon is trying to offer us an even bleaker, more despairing vision of what we have become — but if he’s that serious about it, why then try to deliver it through his chosen portal of a suspense thriller? It can be done, of course: witness the transcendent moral issues raised by Graham Greene in The Third Man or Joseph Conrad in The Secret Agent — both works of A-level calibre, which Butcher is not — but it’s equally possible to try to have your cake and eat it and fail resoundingly.

Indeed, some aspects of the script make little sense psychologically and show a somewhat cavalier attitude towards narrative logic — defects that perhaps would not matter in a piece with more modest aspirations than this one. Butcher offers a variation on an immensely durable dramatic situation — the impact of past misdeeds on the present — and Billon, to his credit, does seem to be attempting to make some sense out of the horrors of recent events in Eastern Europe. But the sensibility of Butcher — at least in this production anyway — ends up devaluing that currency.

There are parallels here to Death And The Maiden, Ariel Dorfman’s unsettling 1990 play about one woman’s appalling attempt to the avenge the viciousness of Chile’s monstrous Pinochet regime. That play, despite being less than a complete success, did raise genuinely troubling questions about the morality of retribution. That same question, if actually lurking somewhere in Butcher, can’t easily surface amidst the scriptural contrivances and melodramatic excesses that too often threaten to take over the GCTC stage.

Yet, there are creditable performances. John Koensgen, who has already portrayed Josef in other cities, is a gifted enough actor to start sculpting a character out of silence and the most minimal body language. It almost seems as though we’re watching a piece of human wreckage breaking up on the rocks of recent history — until this old man is suddenly aroused to a primitive outburst of anger and contempt that scorches in its intensity. Jonathan Koensgen, this veteran actor’s son, also makes a powerful impact as the young lawyer who makes the mistake of his life in showing up at the police station. Working with material whose emotional credibility often seems threadbare and contrived, he manages to make his character’s moral anguish palpable. Sean Devine, required to go an extra mile in ensuring that Detective Lamb is a cop we can empathize with, meets his challenge well. But Samantha Madley’s interpreter lacks an inner life. Her character is important to the play, but in situations where burning rage is called for, along with a moral passion that has become unhinged, we get a smug, self-satisfied, strutting, superficial ice queen. But again, the role as written may be unplayable.

Aspects of the production do seem out of control. There is a death scene that is supposed to be horrific but is so prolonged that it reminds one how Alan Bennett, Dudley Moore and their chums from the Beyond The Fringe satirical troupe were parodying such over-the-top moments more than 50 years ago.

This is also a play that seeks to shock us with a torture scene, and it’s not enough that the victim has to be tied to a chair before the nastiness begins. There has to be a gag in place as well — and amidst the messy, primitive emotions fuelling this play, one would think that a scarf, handkerchief or strip of adhesive would do the trick. But no, it seems that’s not enough to give the evening a few extra kicks, so someone from the theatre’s props department has has apparently trotted down to the nearest sex shop for a state-of-the art ball gag from the store’s S and M section. Presumably the on-stage demonstration of this device’s attributes marks some kind of first in Ottawa theatre. It will no doubt have bondage fetishists in the audience quivering with excitement.