Tolstoy’s “Family Happiness” masterfully adapted and directed by Piotr Fomenko

Photo: A. Kharitinov

Family Happiness, which played at Boston’s Cutler Majestic Theatre on January 26 and 27, is an extraordinary production. Adapted from Tolstoy’s novella of the same name by Russia’s renowned late director Piotr Fomenko, who also staged it, movement and text are given equal value. Although Family Happiness has a much simpler plot, particularly in the staged version, it bears a resemblance to Tolstoy’s later novel, Anna Karenina, which also examines marital happiness and unhappiness. But where the novella is realistic, the play is abstract and symbolic.

It tells the story of Masha and Sergey’s relationship from courtship through the happy days of early marriage to compromise, disappointment, and perhaps resignation. As in the novella, Masha, played by the extraordinary and lovely Ksenia Kutepova, narrates the tale, which unlike Tolstoy’s work is achronological. Fittingly, as the sometime high-energy, sometime dejected, but always self-dramatizing Masha, Kutepova expresses the character through her body.

Although the play moves from Masha’s childhood house to her garden, to her husband’s country estate, Saint Petersburg, and Baden-Baden, the set remains unchanged. Realistic in style, it represents a minimally furnished living room with most of the furniture shrouded in sheets. Upstage there is a raised indoor terrace with three French doors leading to the outside; each side wall has two more doors. All are covered in white drapes. Below the terrace is a seldom used love seat. Two pianos are prominently placed, but scarcely played, although lyrical background music is heard. Four piano stools and several small tables complete the furnishings. The impression is of desolation and/or concealment.

Both acts begin with a veiled Kutepova, dressed in a long coat and large black hat, coming down the aisle, making hissing and hushing sounds, looking like a Halloween witch or the Russian folkloric Baba Yaga. She mounts the stage, crosses to the table down right, and removes her hat with a graceful gesture, indicating a transition. An elegant woman stands before the audience. A middle-aged man, her husband Sergey (Alexy Kolubkov), enters carrying a suitcase and puts it downstage center, where it remains for the rest of the act. This is Masha’s homecoming. They stand, each with a candle in hand, as she goes through a litany of complaints beginning, “Why did you give me so much free rein?” The lights go down.

When they brighten, she is seventeen and the picture of adolescent desire. Dressed in white, she moves about the stage laughing, whirling, dancing, and running from one piano to another. She jumps over the valise, rushes upstage to open the drapes and back down, and again over the valise, to sit on her piano stool and address the audience. She talks of voices, songs from her childhood, and the dreams she had, which reality turned into a nightmare. Masha’s feelings, fantasies, memories, and thoughts are enacted as moving images.

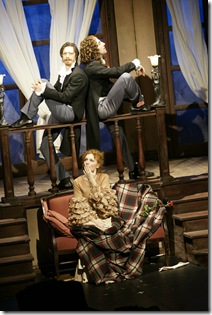

An orphan, buried in the country with her old nursemaid Katia (Galina Tyunina) for company, Masha does not appear to have any male companionship other than Sergey, a friend of her deceased father. Almost twenty years her senior, Sergey is rational, stolid, settled, and ambivalent about Masha. Filled with eroticism, she flirts playfully, and sometimes dangerously, with him in ways that portend their future. In one scene, she laughingly hands him grass, flowers, and leaves to touch, smell, and taste as if to awaken him to sensuality. In another, they are on ladders picking cherries. When he descends, Masha deliberately pushes off the ladder, falls backwards, and is caught by Sergey who collapses on the ground. In still another, she becomes entwined in the terrace balustrade and is freed by Sergey. Without the use of dialogue, these moments tell the audience what is transpiring emotionally within the characters.

Now and again, the characters sit quietly and passively and it is as though we had entered a play by Chekhov, directed by Stanislavsky. Underscoring the Stanislavsky quotation, bird song is heard when Sergey returns in the spring. Passivity turns grotesque when Masha, Sergey, and Katya take tea together, which occurs on several occasions. Sergey puts the tea cozy – a doll which resembles Masha – on his head. They unwind the tablecloth, and use it as a communal napkin. Masha ties her section round her neck, implying her inability to escape.

In Act 2, she is married to Sergey and living on his estate. Marriage brought two happy months for both. But because, as Sergey says in the novella, Masha wants amusement, they move to Saint Petersburg, whose very name conjures up excitement for the young woman. Kutepova draws out the word Saint Petersburg in a dreamy voice while imagining its social whirl. Masha’s fantasy evolves into a dance with two men.

In Saint Petersburg, Masha and Sergey realize the depth of their disillusionment with their marriage. She finds him dull; he is disappointed by her lack of interest in their child. Sitting at her table and wearing her hat, she confides to the audience that the real life that she had been waiting for did not begin when she married.

Masha searches it out at a spa in Baden-Baden where she becomes the leading light for a while. Older, more sophisticated, but not very much the wiser, she loses her social rank to a Lady Sutherland (Galina Tyunina) who appropriates it by singing a French chanson. Masha takes up with two dissolute dandies, an Italian and a Frenchman. They preen and pose in dance-like positions. Trying to regain her place in the limelight, she sings to them in a tremulous voice. In lieu of hitting the high notes, she essays her charm, shrugging and waving her hand in the air. The men dance with her and play with her body, tossing it back and forth. Blackout.

The last scene returns to the beginning. Masha and Sergey are back at her childhood home. She issues the same recriminations, blaming Sergey for her downfall. Katya wheels a baby carriage through one door and out another as she has done twice earlier. Masha, Sergey, and Katya repeat the tea ritual. Masha turns her back on Sergey who is trying to amuse her with the tea cozy.

Family Happiness

In Russian with English supertitles

A production of the Moscow Theatre-Atelier Piotr Fomenko

Adapted from the novella by Leo Tolstoy

Adapted and Directed by Piotr Fomenko

Masha – Ksenia Kutepova

Sergey Mihailovich – Alexey Kolubkov

Katerina Karlovna – Galina Tyunina

Gentlemen at St. Petersburg Ball – Ilya Lyubimov and Kirill Pirogov

Mario, and Italian marquis – Ilya Lubimov

His friend, the Frenchman – Kirill Pirogov

Lady Sutherland – Galina Tyunina

Scene Design – Vladimir Maksimov

Costume Design – Maria Danilov

Lighting Design – Vladislav Frolov

Music Director – Galina Pokrovskaya

Choreographer – Valentina Gurevich