Reviews from Stratford 2015: Stratford Delivers a Richly Involving Carousel

Photo: David Hou

STRATFORD, Ont. — In the 70 years since its lustrous Broadway premiere, Carousel has come to be regarded as Rodgers and Hammerstein’s ‘problem’ musical, a show now tarnished by controversy over its attitude towards domestic abuse.

The indictment isn’t really fair, arising as it does from the dark-textured nature of the romance between swaggering carnival barker Billy Bigelow and the sweet and devoted Julie Jordan. To be sure, Billy’s hot temper is at the core of the story, and with it the revelation that he has struck Julie — only once, she insists — after only two months of marriage.

Inflammatory stuff in our 2015 culture — the sort of subject matter that, by its very mention, can trigger a knee-jerk condemnation from those who don’t even know this show.

However, Carousel’s integrity is convincingly reaffirmed in the production that opened last weekend. And in her notes in the printed programme, director Susan Schulman deals forthrightly with charges that the show condones domestic abuse by giving us a Julie whose love is unconditional. There are complex dynamics at work in any personal relationship — complexities certainly present in Carousel, a ground-breaking musical that, through the medium of popular culture, was tackling the problem of spousal abuse decades before it was being taken seriously in the courts.

(And, it might be noted, Carousel takes this problem far more seriously than Shakespeare’s Taming Of The Shrew, a comedy in which a husband is quite ready to starve his rebellious wife into submission, and which is also part of the 2015 Stratford playbill.)

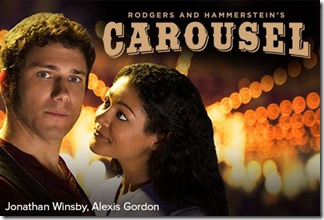

The plight of Julie Jordan, who is beautifully portrayed in this production by Alexis Gordon, can strike a familiar chord with anyone following current headlines dealing with domestic violence and the reluctance of so many women to leave bad relationships. But only the most blinkered critic of Carousel could argue that Oscar Hammerstein ll’s book is a whitewash of a critical social problem. At its heart, Carousel is a dark fantasy about an imperiled marriage, and — in a dramatic departure from music theatre conventions — it gives us a terribly flawed hero who dies through his own recklessness halfway through the second act and then is offered the possibility of redemption by a heavenly starkeeper.

Admittedly, Billy gets a better break than the central figure in Liliom, the Ferenc Molnar play that inspired Carousel; in the original, the carnival barker is consigned to hell as a result of his failure to return to earth and make amends. Rodgers and Hammerstein, for all their readiness to examine touchy social issues, also had a fundamental belief in human goodness — so maybe, just maybe, Billy will have the chance to escape the fiery pit.

So, unless we’re determined to be totally implacable towards Billy, who emerges in Jonathan Winsby’s portrayal as an unhappy and immature young husband tormented by his own sense of uselessness, we can’t easily dismiss Carousel as some sort of cop-out. It is the most troubling and complex musical Rodgers and Hammerstein ever wrote. It also may well be their best. Certainly, it contains their finest score — The Sound of Music, which is also running at Stratford this summer, pales by comparison.

Its historical importance is also unassailable, marking a further advance in the revolution in musical theatre set off by this legendary team with the unveiling of Oklahoma two years previously. For example, there’s the unexpected presence of the swirling Carousel Waltz at the beginning — not a conventional overture but the springboard for a colorful tableau of a Maine fishing community at carnival time. Director Susan Schulman, who has always had a penchant for colorful visual statements, excels herself here with an eye-catching pot-pourri that includes a man on stilts, a bearded lady and a bouncing bear, and then culminates in the sudden delight of a revolving carousel coming into miraculous silvery existence before our very eyes.

The sequence also is a testament to the outstanding involvement of Schulman’s creative colleagues — choreographer Michael Lichtefeld, set designer Douglas Paraschuk, costume designer Dana Osborne and lighting designer Kevin Fraser.

And we mustn’t forget the vital contribution of musical director Franklin Brasz in safeguarding the glories of Richard Rodgers’s music and repeatedly giving us many dazzling moments. Yes, there was a bit of wobbly intonation opening night, including a strangled high note on one occasion. But one mustn’t quibble. Brasz and his musicians are providing admirable support to a cast coping superbly with an intricate and often demanding score. Indeed, by the time Jonathan Winsby’s Billy and Alexis Gordon’s Julie bring If I Loved You to its stunning conclusion, they have passed a major test. With this glorious song, Rodgers and Hammerstein were audacious enough to employ the devices of opera to create a lengthy amalgam of dialogue, recitative and aria — and to give it a dark, forbidding beauty that hints of tragedy. If I Loved You couldn’t be better served by Gordon’s soaring, confident soprano, coupled with a luminous awareness of character. Winsby, whose role is less nuanced in its conception, nevertheless contributes splendidly to the powerful vocal chemistry that the song demands from those who perform it.

It’s a bit of struggle early on for Winsby to define his character and get beyond a robust physical presence. But the opportunity comes with another of the show’s groundbreaking moments. It’s the piece known as the Soliloquy, unprecedented in form — a dramatic musical reverie triggered by Billy’s discovery that he’s about to become a father. Winsby is dealing with a miniature drama in song here, and out of this long, long number he leads us more deeply into Billy’s conflicted, fearful heart.

Winsby makes it a showstopper. He did have a couple of difficult moments with this number opening night, but he can claim to be in good company. Frank Sinatra once admitted that the Soliloquy was perhaps the most ferociously demanding song he had ever encountered and that he had spent days in the recording booth trying Richard Rodgers’ intricate rhythmic changes and maddening modulations right

The bottom line is that Winsby and Gordon are an attractive and responsive pair of leads: they honor the score and also have the dramatic chops to bring credibility to some highly emotional moments in the second act. Still, there is the sense that they’re trapped in a rather old-fashioned production — one which, for example, often seems content to have characters singing out to the audience rather than to each other, and in which the staging of some musical numbers seems slickly formulaic rather than fresh. Yet, the power of the music and the individual performances keep rescuing the production from its occasional stiffness. And the big set pieces — the opening waltz, If I Loved You, the big second act ballet — are memorably executed.

The futuristic ballet scene is a stunning achievement, dominated by the feisty yet forlorn presence of Billy’s teenage daughter, Louisa, who is eloquently danced by Jacqueline Burtney. In its time it was another radical Rodgers and Hammerstein innovation — but it was also germane to the redemption of Billy whose shade is watching his troubled daughter from the sidelines.

This production boats a succession of solid supporting performances — highlighted by Evan Buliung’s superb work as Billy’s low-life buddy, Jigger Craigin, and by Alana Hibbert’s emotionally shattering rendition of You Never Walk Alone, a song that makes Climb Every Mountain seem like an also-ran. Further pleasures are provided by Robin Evan Willis as the perky Carrie Pipperidge and Sean Alexander Hauk as her bashful beau, Enoch Snow. It’s a bit much to have Ian Simpson’s Starkeeper glide into view on an oversized silver horse, and Simpson seems a bit uncomfortable serving as Billy’s celestial conduit to possible salvation, but his performance too serves a purpose.

The bottom line is that this is a richly involving production of a musical that took big risks in both form and content. It deserves an audience.

(Carousel runs to Oct. 11. Ticket information at 1 800 567 1600 and stratfordfestival.ca)