La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast): A visual treat that falls flat dramatically

Photo: Yves Renaud

For the second time this season Boston’s ArtsEmerson is playing host to a Montreal troupe. Early fall saw the return of Les Sept Doigts de la Main, a hybrid company that explores links between theatre and circus. December began with the experimental Lemieux Pilon 4D Art’s presentation of its intermedial La Belle et la Bête, complete with an updated plot.

Onstage actors relate to and with virtual ones. Of the three live characters, the Lady (Diana D’Aquila), Belle (Bénédicte Décary), and the Beast (Vincent Leclerc), only the latter appears in computer generated form, and then rarely. Belle, the young alienated artist usually dressed in black, attempts to work through the loss of her mother by hurling blood red paint at canvasses. The Beast, grief stricken because of the death of his beloved years earlier, lives alone in a castle metaphorically worlds away from Belle’s studio. His ugliness is barely suggested by facial scars, too faint to be seen by audience members sitting at a distance from the stage.

In contrast to Belle, the Beast is clad in a lavish gold, bronze and red robe, a hood masking his face at first. The colors of his costume reference Henry Fuseli’s painting of “The Nightmare,” the production’s initial projected image. A woman apparently asleep lies on a bed, her body twisted, a demon crouched above her and a black horse’s head in the background. The enigmatic Lady, part-fairy, part-witch, tells us that there is always a monster somewhere ready to slit a princess’s throat. That she is the monster remains a mystery until the end

We discover the Beast was a poet in his former life. Belle compliments him for his ability to puts words to what she is feeling. The Beast admires her art. But apart from these few moments, little is made of what might have been an investigation of the literary and visual arts as personified in these two characters.

Creators Michel Lemieux and Victor Pilon’s greater interest in the visual is reflected in the spectacular imagery and imaginative interplay of the virtual and the real, a technological feat in this production. Traditionally, Belle is the victim of two jealous sisters. Here Anne-Marie Cadieux portrays one sister who appears in three incarnations, miniscule, gigantic, and in one brief scene, normal-sized. In a two-way dialogue, they function as alter egos, the large one berating Belle, the small one complimenting her. Peter James plays iterations of the filmic demon.

A magical rainstorm fills the stage and part of the theatre; glass breaks into diamond-like shards, trees transform into twisted brambles, to mention only few of the beautiful illusions.

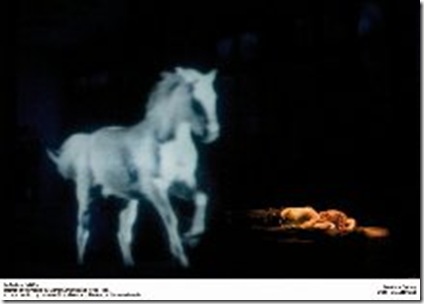

Although the creators take pride in the modernity of their technology, the influence of Jean Cocteau’s 1946 surrealistic film of the same name is obvious. The recurring virtual white horse which Belle follows to the Beast’s lair brings to mind le Magnifique, Cocteau’s magic horse. The slow-moving projected statue in the Beast’s courtyard recalls Cocteau’s multiple animated sculptures. Other symbols used by Cocteau and incorporated into the Lemieux/Pilon production include a mirror, glove, and fire.

Michel Smith’s modernist musical score is thrilling, sometimes sensual, and reminiscent of Philip Glass’s 1994 operatic version, originally meant to replace the film’s soundtrack.

As opposed to the sleekness of the visual, the plot is clunky and the backstory hard to follow. The protagonists meet when Belle delivers the rose of a stone medallion to the Beast. As expected, the two are both drawn to and fear each other. Belle wants to see the Beast’s face; he wants one of her paintings. Both are afraid of revealing themselves. Ultimately, the Beast lowers his hood and grants her permission to paint him if she submits to him sexually. She flees, only to return.

The Beast gives her a luxurious robe and then drugged tea. They dance together whirling faster and faster until she falls onto the bed in the same position as the woman in Fuseli’s “The Nightmare.” The Beast begins to undress her, stops, and mist fills the room.

While this scene, like most of the others, is appealing to the eye, it is dramatically silly and heavy-handed, in large part because of the pretentious and vapid dialogue that permeates the entire play. Contemporizing the characters adds little, since they are left undeveloped. La Belle et la Bête ends as it began with the Lady’s pseudo-philosophical questions, “Who am I? Who are you?” Questions that have little to do with the events of the play.

The acting was generally weak. Belle and the Beast demonstrated little passion for each other. Classical actress Diana D’Aquila spoke beautifully, but seemed distanced from the role even when revealing her loathing of Belle. They were given scant help by playwright Pierre Yves Lemieux who failed to create suspense or the two directors who offered them little guidance. Technological wizardry notwithstanding, the directors were unable to develop a psychologically convincing drama.

ArtsEmerson presents Lemieux Pilon 4d art Production of La Belle et la Bête

Created and directed by Michel Lemieux & Victor Pilon

Written by Pierre Yves Lemieux

Composed by Michel Smith

Translated by Maureen Labonté

Visual Designers: Michel Lemieux & Victor Pilon

Set, Costumes and Props: Anne-Séguin Poirier

Visual Co- Designer: Mathieu St-Arnaud

Make-up Designer: Jacques-Lee Pelletier

Lighting Designer: Alain Lortie

Cast

Belle ………. Bénédicte Décary

The Lady ….. Diane D’Aquila

The Beast …..Vincent Leclerc

Virtual Characters

The Sister ….. Anne-Marie Cadieux

The Demon … Peter James

The Horse ….. Champagne, trained by Azalée Gaudreau

La Belle et la Bête plays at the Cutler Majestic, Boston, MA unt