Despite fine performances, Fierce is a play built on sand

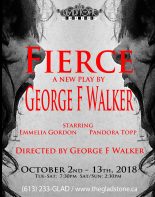

Fierce by George F. Walker. A Black Sheep productions

Gladstone Theatre to Oct. 13

You have to be careful with George F. Walker. The outward trappings of his plays can be so dramatically enticing that they can fool you into thinking you’re watching something good.

This prolific Torontonian knows how to set up a situation bristling with potential. And in the case of his recent play, Fierce, now at the Gladstone, it has to do with a psychiatric session that is driven off the rails by the patient. So yes, the idea is promising.

Walker also has an engaging ear for language, and his writing crackles with the kind of naturalistic dialogue that can seduce us into the world of his plays. It can be argued that playgoers aren’t getting a real world here; rather they are being ushered into Walker’s own restless landscape of the imagination. But no matter — major Walker successes like Zastrozzi, Theatre Of The Film Noir and Nothing Sacred show that it can be a weirdly credible landscape, albeit anchored to its own skewed reality.

But what of the credibility factor when it comes to Fierce? Let it be said immediately that this Black Sheep two-hander features outstanding performances from Pandora Topp, as an uptight psychiatrist named Maggie, and Emmelia Gordon as the patient who turns the tables on her. These two are compelling, but they are nonetheless attempting a salvage operation on problematic dramatic material.

Gordon supplies some volcanic moments as Jayne, a totally messed-up drug addict referred by the courts for psychiatric treatment after she suicidally walks into heavy traffic. She is Walker’s chosen vessel for the threads of bleak, black comedy that are a recurring hallmark of his plays. But the main impact here is the churning inferno of emotions that Gordon unleashes — despair and anger in equal measure plus defiance, self pity and a manipulative cunning that is awash in lies. She possesses all the elements of someone out of control — but it’s not that simple when it comes to someone like Jayne.

Suddenly you realize that she’s the one in control. She’s the one who browbeats Maggie, the psychiatrist, into coming clean about her own troubled past. It’s the price that Maggie must pay for getting Jayne to cooperate.

And increasingly, as this 75-minute play unfolds, it’s difficult to believe any of it. That’s a pity, given that Walker, a dramatist often accused of brittleness, seems to be writing from the heart here.

The fashion jeans worn by Pandora Topp’s Maggie suggest a trendier version of modern psychiatry, which may make lovers of prime-time TV happy, but it doesn’t necessarily make this character more plausible. But Topp, already taut as a board when we meet her, is very good at generating an inner tension. Her discomfort over Jayne’s verbal onslaughts and threatening body language is evident from the beginning. She is palpably in fear of losing control over the situation — and as the play progresses she does.

But for all Topp’s care in fashioning the character of Maggie does she really add up? Our scepticism is in full rein by the time Jayne takes the initiative, figuring that the best way for both of them to lower their defences is to take LSD and consume vast amounts of vodka. Maudlin drunk scenes are tiresome enough in most plays. Maudlin hallucinatory drunk scenes are even worse — and at this point we’re legitimately asking ourselves how someone as vulnerable and malleable as Maggie ever found herself entrusted with the care of someone like Jayne. But no, we might better ask how on earth did she ever get accredited as a psychiatrist in the first place? We’re in fantasyland, folks.

Walker is attempting his own variations on a couple of overworked themes. One is role reversal — but Walker is no Ingmar Bergman. The other theme has to do with the psychiatrist who takes on a severely troubled patient only to end up personally in a state of professional and emotional crisis. But classic works like Peter Shaffer’s Equus, Joe Penhall’s Blue/Orange and Nigel Balchin’s Mine Own Executioner travel a psychologically convincing arc. They scrupulously avoid the contrivances evident in Fierce.

The bottom line is that despite its psychiatric pretensions, Fierce is simply another of those plays about confronting one’s demons. The devices are basic. Rip away scabs of denial. Subject the characters to a series of bruising revelatory moments. At the end sign off with catharsis and a fragile but emotional closure.

All very nice and uplifting if we believe it. But can we — really? Not by a long shot.

Director: George F. Walker

Lighting: Steven Lafond, Dave Dawson

Set Design: Dave Dawson, Christopher Mathieu

Maggie: Pandora Topp

Jayne: Emmelia Gordon