Cabaret at the Shaw Festival: Director Peter Hinton Goes the Phantasmagoric Route For a World that Emerges From the Dying Embers of the Weimar Republic.

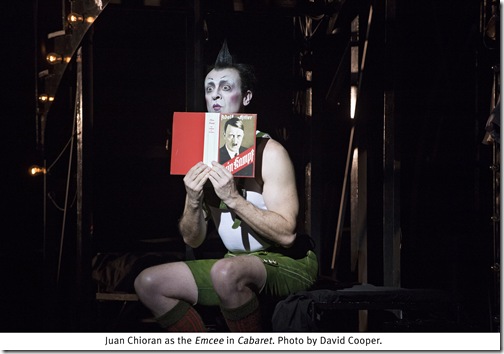

Juan Chioran as the Emcee. Photo by David Cooper.

NIAGARA-ON-THE-LAKE, Ont. — You can’t be entirely sure what is happening in the final sombre moments of the Shaw Festival’s production of Cabaret. Indeed, there’s the suggestion that Cliff Bradshaw — the expatriate young American who has come to pursue a writing career in Berlin amidst the dying embers of the Weimar Republic and the rising tide of Nazi Germany — won’t make it home safely. After all, we last see him engulfed in the hellish inferno of designer Michael Gianfrancesco’s skeletal set.

The latter, looking like something lifted out of a Fritz Lang film, is an ominously ambiguous concoction of steps and scaffolding, of blinking lights and yawning voids. It can morph into the infamous Kit-Kat Club — although it’s not really the Kit-Kat Club we have known in previous treatments of this classic musical — or it become Fraulein Schneider’s boarding house — although again it’s doesn’t seem quite right because there’s something fragmented, even intangible, about the way its overlapping worlds are presented to us.

This metallic hulk is on a revolving platform which is put to eerie use in Peter Hinton’s fascinating production. Indeed, there are times when Cliff, the inimitable Sally Bowles, Fraulein Schneider and her amorous German suitor, the aging greengrocer, Herr Schultz, even the demonically driven Emcee of the club, seem prisoners on an spectral carousel which at the end becomes silhouetted against a blood-red sky.

You can thank Hinton, Gianfrancesco, and lighting designer Bonnie Beecher for the arresting look of the show. But it does force unfortunate trade-offs when it comes to staging some of the action. In particular, given the dominance of the set, choreographer Denise Clarke has a tough time in such environs to make much of an impact with the show’s dance numbers — although the tackiness and ennui displayed by the cavorting Kit-Kat girls do exude a seedy authenticity.

In a sense, Cabaret is a musical that eludes easy definition. It carries not just the shifting imprints of Christopher Isherwood’s original Berlin novels, playwright John Van Druten’s stage adaptation under the name of I Am A Camera, and the creative team that then turned it into a musical — Joe Masteroff (book), John Kander (music) and Fred Ebb (lyrics). It also shows the variable influences of its major directors — Hal Prince, who first mounted it, followed by a radical rethinking from Sam Mendes and Rob Marshall.

Under Hinton’s direction, Cabaret becomes a phantasmagoric tone poem in which reality and fantasy bleed into each other. The Kit-Kat Club, as always, remains a metaphor for human horrors, past, present and future — but this time the growing desolation and hopelessness, those glimpses of the skull beneath the skin, seem more pronounced. Those sad, pasty-faced, androgynous inhabitants of the Kit Kat Club are half-dead already. And when Deborah Hay, absolutely brilliant in the role of that amoral, apolitical good-time girl, Sally Bowles, swings into the title number to tell us that “life is a cabaret” she is ruthless in exposing the vulnerability which Sally has long suppressed. It’s a defiant show-stopping performance of one of musical theatre’s greatest songs, but the defiance is tinctured with a terrible despair. Sally has been forced to acknowledge the gathering storm.

Under musical director Paul Sportelli, John Kander’s great score is allowed to reveal its virtuosity, its dark tonalities often reflecting the sardonic sensibility of a Kurt Weill. And the cast responds splendidly to both Cabaret’s musical and dramatic needs.

Hay, equally home in drama and musical theatre, gives us a Sally for the memory books — sexy, funny, exasperating in her self-absorption and ultimately affecting. She;s dynamite. Gray Powell manages to make the character of Cliff less of a bland non-entity than is often the case with productions of this show. Corrine Koslo is powerful and moving as Fraulein Schneider, who finds herself too much of a “good” German to risk continuing her relationship with the Jewish Herr Schultz, portrayed with doomed devotion by an excellent Benedict Campbell.

As for Juan Chioran’s Emcee — our leering and brutal confidant, the assured ringmaster, the hellish manipulator of emotions, including our own — his characterization is almost wraith-like. But that doesn’t make him any less formidable — not when he’s the stuff of which nightmares are made.

(Cabaret continues at the Festival Theatre to Oct. 26. Ticket information at 1 800 511 7429 or shawfest.com)