All the Way falls short at Cambridge’s American Repertory Theatre

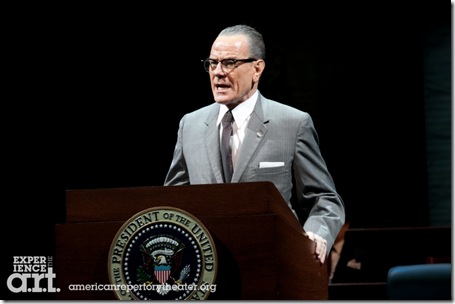

Bryon Cranston. Photo by Evgenia Eliseeva

All the Way, currently playing at Cambridge’s American Repertory Theatre (ART), was originally produced by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival as part of its project to explore U.S. history. “American Revolutions: The United States History Cycle,” is commissioning up to thirty-seven new plays of differing styles and genres that tackle significant moments of political and/or social change. Thirty-seven, the number of Shakespeare’s plays, alludes to the kind of characters the Festival hopes the project will create.

And, in Lyndon Johnson, the protagonist of All the Way, playwright Robert Schenkkan has indeed focused on a figure of Shakespearean stature. Johnson, an egocentric power player, was responsible for the most far-reaching liberal social reforms, since Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Despite his legislative success, Johnson authored his own downfall through his prosecution of the Viet Nam War. The paradoxical Johnson still looms over U.S. politics at a time when Republicans seek to eradicate his social programs while Democrats fight to maintain them.

Schenkkan’s documentary drama presents the first eleven months of Johnson’s presidency, beginning with a nightmare after Kennedy’s assassination and ending with his electoral triumph over conservative Barry Goldwater in 1964. It is a play packed with events and characters. Seventeen actors enact forty-five characters with only television star Bryon Cranston (Lyndon Johnson) and Brandon J. Dirden, (Martin Luther King) playing single roles. As a result, many characters are undeveloped and/or conventionalized. This is particularly true of the female characters, played by just three actresses. (Was it the playwright’s intention to replicate the era’s misogyny by paying so little attention to women?) Schenkkan and director Bill Rauch give us a Lady Bird Johnson (Betsy Aidem) who is mostly cringing and adoring, in one scene kneeling to put on her dismissive husband’s shoes. Susannah Schulman’s Lurleen Wallace and Muriel Humphrey beam at their respective husbands.

Lyndon Johnson scarcely leaves the stage throughout the play; his many scenes are interspersed with monologues to the audience. Bryon Cranston has the dynamism, charisma, and craft to involve the audience of fans in the politics of that era, although most were too young to have lived through them. Although he does not have a strong resemblance to Johnson nor sound very much like him, Cranston is convincing as the master of manipulation, wheedling, promising, threatening as needed. He plays the humor for all its worth with impeccable timing. Missing is Johnson’s complexity, his motivation for putting his career and the future of the Democratic Party on the line for the sake of civil rights. In all fairness, the script does not aid him in this respect.

Dirden captures Martin Luther King’s distinctive vocal rhythms, but not his magnetism. Surprisingly, he is something of a minor player here. It may have been Schenkkan’s design to diminish King’s role in order to give greater emphasis to other Black civil rights activists such as Ralph Abernathy (J. Bernard Calloway) and Stokely Carmichael (William Jackson Harper), but it unbalanced the play.

Christopher Acebo’s multipurpose setting, dominated by three upstage banks of benches, calls to mind both a legislative chamber and a courtroom. During the performance, various actors sit watching the proceedings taking place in front of them as if witnesses to history. Although an effective metaphor, the benches limit the blocking. Projections provide added visual context for events being discussed or occurring onstage. Apart from the projections and the massive oaken benches, the only note of color in the set is turquoise. A large oval turquoise rug in front of the benches is the main playing area. Johnson desk chair is upholstered in turquoise; other chairs are trimmed in turquoise.

Deborah M. Dryden’s costumes successfully portray mid-twentieth-century officialdom. The politicians’ suits are appropriately drab and ill-fitting, while the women, garbed in brighter colors, are equally lacking in style.

Schenkkan has researched and mined a fascinating piece of history. If there is an overriding flaw, it is that it includes too much and yet not enough. Numerous side plots clutter the central story. And while the first act principally deals with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the second concentrates on Johnson’s presidential campaign, terminating shy of the passing of the Voting Rights Act, the natural ending to the tale.

Written by Robert Schenkkan

Directed by Bill Rauch

Set Design Christopher Acebo

Costume Design Deborah M. Dryden

Lighting Design Jane Cox

Composer / Sound Designer Paul James Prendergast

Projections Shawn Sagady

|

Cast |

|

|

Bob Moses/ David Dennis |

|

|

Lady Bird Johnson/Katharine Graham/Katharine St. George |

|

|

Hubert Humphrey/ Strom Thurmond |

|

|

Robert McNamara/ James Eastland/ William Moore McCulloch/Paul B. Johnson, Jr. |

|

|

George Wallace/ James Corman/ Joseph Alsop/ Mike Mansfield/ Walter Reuther |

|

|

Ralph Abernathy/ Butler |

|

|

Lyndon Baines Johnson |

|

|

Coretta Scott King/ Fannie Lou Hamer |

|

|

Martin Luther King, Jr. |

|

|

Roy Wilkins/ Shoeshiner/ Aaron Henry |

|

|

James Harrison/ Stokely Carmichael |

|

|

Richard Russell/ Emanuel Celler/ Jim Martin |

|

|

J. Edgar Hoover/ Robert Byrd |

|

|

Walter Jenkins/ William Colmer |

|

|

Stanley Levison/ John McCormack/ Seymore Trammell/ Edwin King |

|

|

Cartha DeLoach/ Howard Smith/ Everett Dirksen/ Carl Sanders |

|

|

Secretary/ Lurleen Wallace/ Muriel Humphrey |